How These Contemporary Artists Are Redefining Family and Kinship

Smithsonian Magazine

By Shantay Robinson

Explore the enduring bonds and intimacies of modern love at the National Portrait Gallery

In the self-portrait, the artist is holding their baby behind a screen door; in their eyes is a look of intense love, and their tender embrace of the child is deeply moving. The 2018 photograph by Jess T. Dugan, titled Self-portrait with Elinor (screen), depicts the typical adoration of a parent for a child, but the image is especially profound because Dugan is gender nonbinary, and their partner is a cisgender woman.

“In my practice, I’ve always fused a classical style of photographing with a very contemporary subject matter,” Dugan says. “And that’s a strategy I use to bring attention to queerness and different kinds of identity when thinking about sexuality.” Dugan’s art is among more than 40 stunning works on view in the new exhibition “Kinship,” now on view at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

The paintings and images in the show embrace new approaches to portraiture, once a genre of art reserved for the wealthy. And these time-defying photographic series and unconventional painted portraits of those near and dear also demonstrate how the notion of family is changing.

“I think there is this accessibility of the camera that makes for this democratization,” says Leslie Ureña, curator of photographs at the museum. “These artists are taking the medium that can at once seem accessible, but they are making fine art projects that can also trace histories through their works.”

[…]

LaToya Ruby Frazier, who received the MacArthur Fellowship in 2015, found a kindred spirit while producing a photographic essay of the Flint, Michigan, water crisis for Elle magazine.

In 2014, city officials made the decision to switch the town’s water supply from a treated source to a non-treated cheaper alternative, exposing the people of Flint to a staggering increase in the amount of lead in their water. An outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease, a severe form of pneumonia, coincided with the water crisis. Today, the water is deemed safe after hundreds of millions of dollars spent repairing the town’s infrastructure, but residents continue to mistrust the water supply, with many refusing to drink from the tap.

Family doesn’t simply stop at the blood line, it expands throughout culture and society as you meet people.

— LaToya Ruby Frazier

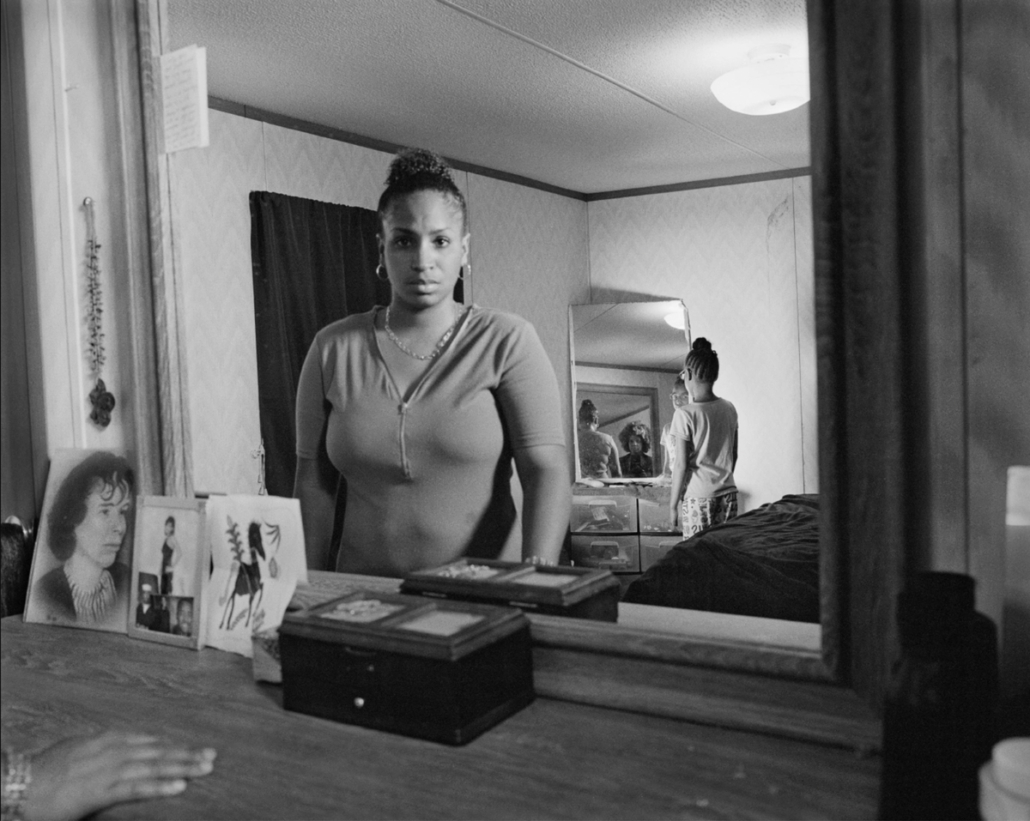

While covering this crisis, Frazier met Flint resident Shea Cobb, a poet and activist. The two formed a deep bond as Black women with a working-class background and a deep commitment to resisting environmental contamination—Frazier describes the relationship as “kindred spirits in two bodies.”

The black-and-white images in this series are observant of how life continues even as environmental disasters infringe on daily activities. Images of the subjects going about their normal routines despite not having basic needs showcase the people of Flint’s incredible endurance.

In one photo, Cobb pours water from a store-bought plastic bottle into her daughter’s mouth, so she can brush her teeth. The image captures the split second when the water flows from the bottle, just before it lands in the young girl’s mouth.

“Flint Is Family In Three Acts,” “The Lams of Ludlow Street” and other photographic series in the show demonstrate the many years these photographers have spent with their subjects, chronicling the extent to which they have become kin. “You can track time in a different way through their projects, through the camera and through their photographs,” Urena argues.

[…]

Courtesy of: Smithsonian Magazine