LaToya Ruby Frazier’s Monument to Empathy

Hyperallergic

by Zoë Hopkins

Though Frazier’s photography is often described as “documentary,” it betrays a thorough investment in and interchange with those she photographs.

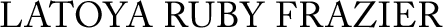

LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Marilyn Moore, UAW Local 1112, Women’s Committee and Retiree Executive Board, (Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co., Lear Seating Corp., 32 years in at GM Lordstown Complex, Assembly Plant, Van Plant, Metal Fab, Trim Shop), with her General Motors retirement gold ring on her index finger, Youngstown, OH” from The Last Cruze (2019) (all photos Zoë Hopkins/Hyperallergic)

Two hands, finely wrinkled and thick at the knuckles, rest one atop the other, gathered together in quiet elegance. They express a keen sensitivity to style: five fingers are ornamented with rings. One of these, worn on the right index finger, is a gold General Motors retirement ring. As I look at LaToya Ruby Frazier’s carefully arranged photograph of these hands, and become fixated on this singular element, this portrait of adornment and self-fashioning expands into a record of the industry that these hands sustained. The ring is indeed imbued with beauty and honor, but it also directs my attention subtly toward fraught questions about the labor it commemorates, and to the sinister reality of the industrial factory. The image conveys the beauty and dignity of these hands, as well as the things they labored over; it pays homage to their work while refusing to reduce them to it.

These hands belong to Marilyn Moore, a UAW 1112 member who worked at General Motors for 32 years. Frazier met Moore while working on The Last Cruze, the artist’s 2019 photo series made in collaboration with members of UAW Local 1112 and 1714 based in Lordstown, Ohio, as they fought against the closure of their GM assembly plant. Moore’s portrait is among the last images in Monuments of Solidarity, a survey of Frazier’s work currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art.

Frazier’s photographs reveal an eye that is at once tender and probing: they stare unflinchingly at the collusion between post-industrial capitalism, environmental racism, and class disenfranchisement, while illuminating with solicitous regard the strategies of refusal and resistance that working-class communities (most of them Black and Brown) have developed in response. Though her photography is often described as “documentary,” it betrays a thorough investment in and interchange with those she photographs that makes it difficult to buy into this designation. Crystal and urgent moral and political clarity breaks through Frazier’s work. Her images are conceived in and through a relational ethic that stretches beyond empathetic storytelling — each photo sutures Frazier to the people she photographs, and their shared struggle to render a more livable world for those ensnared in racial capitalism.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Mom Making an Image of Me” from the series The Notion of Family (2008)

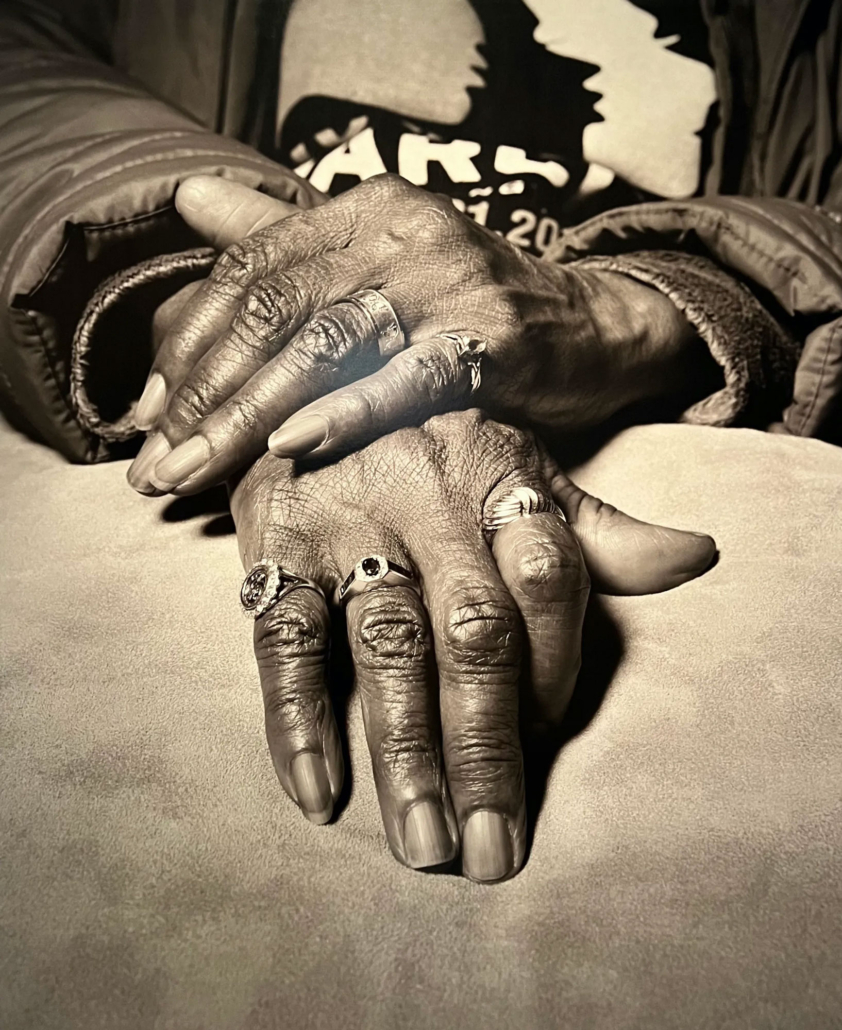

The show begins with Frazier’s earliest work, The Notion of Family (2001-2014), a series shot in the raw interior of her family life in her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Braddock, which was once a mighty steel-industry town, has today morphed into a hotbed of economic devastation, toxic pollution, and consequent medical crises after being abandoned by its purveyors of industry decades ago. These circumstances come hurtling into view in works like “Landscape of the Body (Epilepsy Test)” (2011), a diptych that juxtaposes an image of Frazier’s mother hooked up to a hospital machine with one of the ruins of the demolished University of Pittsburgh Medical Center hospital. (It closed in 2010, leaving patients like Frazier’s mother without a local hospital.)

Such images of injustice mingle with portraits of familial entanglement and resemblance like “Momme” (2010). Here, Frazier gazes head-on at the camera, while her mother is pictured in profile, eyes closed. Their noses and chins meet, drawn together like puzzle pieces. The photo, which already has a quietly affective sting, delivers a heavy emotional blow when read against the image of the artist’s mother in the hospital. Over the course of the exhibition, Frazier’s metaphorical aperture widens from her family to her community, and then to other communities across the United States that have contended with struggles similar to those of Braddock’s residents. Frazier is no outsider looking in; rather, she begins with what she carries inside her and works outward from there.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Landscape of the Body (Epilepsy Test)” (2011)

The exhibition’s title, Monuments of Solidarity, turns on two words that singe with the heat of today’s political climate. It conjures questions underlying the contested idea of the monument in the 21st century. The recent memory of racist monuments across the United States cascading down from their plinths comes flaring up in the mind’s eye.

Though Frazier’s photographs don’t explicitly take on these themes, they hum in the background of works like “Flint Is Family Act III” (2016) (note the titular echo of A Notion of Family). Here, Frazier’s photographs of people affected by the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, are mounted on metal frames and installed in the middle of the gallery like miniature billboards — or monuments. The portraits are paired with transcribed excerpts of oral interviews with each sitter. It is in this dovetailing of the photographic and textual narratives that we might conceptualize a monument, or perhaps a counter-monument that rebukes the messaging sold by monuments to people like Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick, for example, both of whom amassed their vast fortunes from Pennsylvania steel mines.

Installation view of LaToya Ruby Frazier, Flint is Family in Three Acts (2016)

Frazier’s most dramatic gesture to the monument is in The Last Cruze — the same series to which the aforementioned photograph of Marilyn Moore belongs. A hulking, bright orange metal structure stretches across one of the galleries like an elongated, industrial rib cage; black and white portraits of Ohio UAW members are installed throughout the structure, where they are once again paired with narrative testimony about their struggles against General Motors.

The words that bubble up as I navigate this massive sculpture feel somewhat at odds with one another. The structure itself is powerful, titanic, overwhelming, but the photographs are poignant and caring, and deeply reflective of a spirit of solidarity. I begin to wonder: Can the form of the monument, which has so long served to reinforce hierarchy and the authority of the individual, be reconciled with a photographic practice that is so rooted in an ethos of horizontality and collectivity? Or does the struggle that is waged in Frazier’s photographs require a different vocabulary, one that refuses the symbolic heroics of the monument? What, I wonder, becomes possible when we recognize that solidarity might not need the grammar of the monument at all?

Installation view of LaToya Ruby Frazier, The Last Cruze (2019)

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Monuments of Solidarity continues at the Museum of Modern Art (11 West 53rd Street, Midtown, Manhattan) through September 7. The exhibition was organized by Roxana Marcoci, David Dechman Senior Curator and Acting Chief Curator, with Caitlin Ryan, assistant curator, and Antoinette D. Roberts, former curatorial assistant, Department of Photography.

Courtesy of: Hyperallergic