Review: A remarkable ode to union workers in LaToya Ruby Frazier’s ‘The Last Cruze’

Los Angeles Times

Art Review

By Christopher Knight, Art Critic

Unions built the American middle class in the decades after the Great Depression of the 1930s, the common wisdom goes, and a mountain of evidence backs up the claim. Yet things have been bleak in that regard for many years.

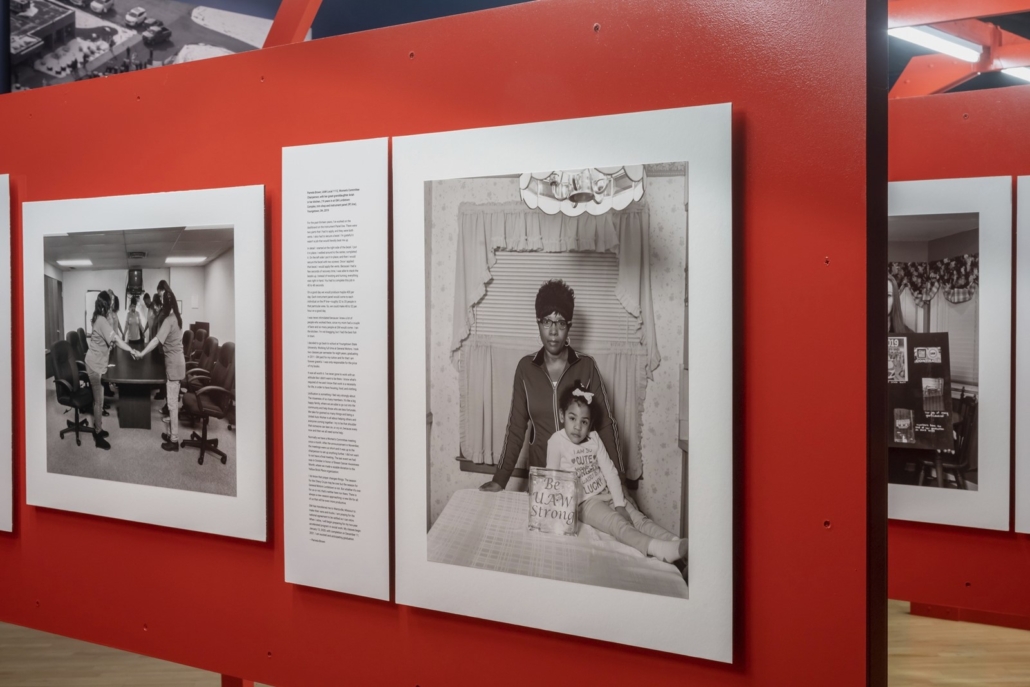

One example is the centerpiece of a keen and moving installation by LaToya Ruby Frazier at the California African American Museum in Exposition Park. “The Last Cruze” charts the devastating 2019 shuttering of a General Motors auto plant in the once solidly middle-class village of Lordstown, Ohio. Frazier, who grew up just outside Pittsburgh, less than 100 miles to the southeast, chronicles the closure’s myriad effects on the workers, most affiliated with UAW Local 1112.

The share of American adults who live in middle-income households tumbled from 61% in 1971 to 51% in the year the GM factory closed, according to the Pew Research Center. Union membership has plummeted to the low teens, a decline that has contributed to the ruinous wealth gap that plagues us today, affecting everything from the crime rate to the functioning of democracy itself.

Famously instrumental to the battering was the Reagan administration’s sudden 1981 firing of more than 11,000 striking workers in the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization. Open season was declared on organized labor.

In her terrific recent book, “The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together,” social justice policy analyst Heather McGhee definitively outlines a different yet plainly related factor, which unfolded over many years: “Somewhere along the line, white people stopped defending the institutions that, more than almost any other, had enabled their prosperity for generations.”

Unions were one fundamental institution where support collapsed. Lately they’ve been witnessing a change of fortune, with President Biden the most pro-union chief executive in decades and art museums (and newspapers) among those creating a unionization boomlet.

McGhee’s persuasive observation, which digs into the racially framed causes for that larger breakdown in general union support, came to mind as I was looking at Frazier’s insightful documentary narrative at CAAM. The installation includes 67 photographs and a video; the array of union workers embodies a multiracial democracy.

The still pictures are black-and-white, a signal for alliance with the tradition of incisive social documentary camerawork launched in the late 19th century by artists like Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine. (Riis documented New York’s rising tide of unemployed and unhoused immigrants, and Hine the brutal child labor once common to profitable industry.) Black-and-white stands outside the usual commercial and vernacular histories, where color photographs have become routine.

The video is in color. Including commentary on the last Chevy Cruze auto to roll off the Lordstown assembly line — hence the show’s title — it suggests television’s increased authority in the documentary genre.

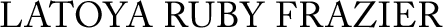

Surprisingly, these documentary camera legacies merge with installation art. These aren’t framed pictures hanging on a wall. To display the photographs, most of them portraits of GM workers whose biographies and work histories are laid out in accompanying printed texts, Frazier built an architectural construction that runs the length of the gallery. The structure gives the show a veritable spine.

Each display panel’s shape is loosely reminiscent of a car door, lined up one after the next. Painted a bright, safety-conscious red-orange, the structure’s repetitive form mimics the machinery of an assembly line. Suspended panels alternate with panels that reach to the floor, yielding a subtly animated visual movement.

Overhead, unadorned fluorescent tubes shine a harsh and unflattering light on the scene. Individual stories in the photographs and texts cover the waterfront — tales of woe, pride, family, despair, friendship, anger, hope, disillusionment and more.

The gallery is painted a midnight blue, which gives the space a hushed aura. (On the day I saw it, others entering the show immediately began to whisper.) The ensemble transforms into a secular church with the assembly line its nave.

On the walls at either end, a large photo blowup focuses on a woman’s worn hands. One hand shows off trinkets that commemorate her work history, the other her GM retirement gold ring. The spine of individual stories links the two. On the side wall between them, an aerial picture shows workers holding signs and standing in a circle around a flagpole outside the factory offices.

The signs read “Drive it home,” part of a last-ditch advertising campaign for the popular, affordable, not especially attractive but soon to be abandoned model of car. Snow covers the ground. It’s a God’s-eye view of wintry stoicism and impending loss.

Off to one side, a small room houses a single bench and the video, projected big on the wall. At first the space seemed too cramped, the huge video projection oppressive, the volume too loud for the workers telling their stories of the factory closure. That sense quickly dissipated, though, as the context shifted the experience.

The little room became a kind of private confessional, adjacent to the “church,” where people on a screen unburden themselves of the complex realities of their situation to people they cannot see.

The video format is akin to that for the still photographs: The stills hang on suspended display walls that leave just a narrow space to accommodate only one or two viewers at a time. You’re physically up close and personal. Going through the lineup, visitors must be mindful of other viewers, adjusting themselves according to movements that are at once communal and individual.

The show was commissioned by the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, and its CAAM presentation is in partnership with the USC School of Architecture and Roski School of Art and Design. It comes with a hefty book that chronicles Lordstown events in great detail, mostly in the words of the people in the pictures.

What’s remarkable about Frazier’s installation is the sense of intimacy it’s careful to create — intimacy that is essential to an empathetic understanding of these workers’ quandary. A certain equilibrium arises between viewer and viewed.

That’s not always the case with socially incisive documentary photography, which has long wrestled with an unexpected conundrum. Seeing photographs can be the passive endpoint of the experience, rather than a spur to action. Frazier’s imaginative merger of documentary camerawork with installation art has found an effective formal language to shift the power balance.

‘LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze’

California African American Museum

Exposition Park

600 State Drive, L.A.

(213) 744-7432

caamuseum.org

Courtesy of: Los Angeles Times