Tony Norman: LaToya Ruby Frazier’s photos are a witness and a mirror

NEXT Pittsburgh

by Tony Norman

One day, artist LaToya Ruby Frazier’s body of work will be considered key to understanding how many Americans learned to look at their fellow citizens with a little more empathy and compassion in the first half of the 21st century.

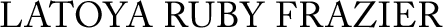

Installation view of LaToya Ruby Frazier, More Than Conquerors: A Monument For Community Health Workers of Baltimore, Maryland, 2021–22. Photo by Sean Eaton courtesy of the artist and Carnegie Museum of Art.

Frazier’s photographs, gallery installations, books and essays resonate with an intensely personal vibe born and bred in Braddock, where she spent her formative years experiencing the effects of the steel industry’s collapse on her family and the community.

The images Frazier highlights in such award-winning works as “The Notion of Family” and “More Than Conquerors: A Monument for Community Health Workers of Baltimore, MD,” — now on view at the Carnegie International through April 2 — invite viewers to wrestle with questions of social and environmental justice, cultural change and healthcare equity in their own communities and across the nation.

Just as Gordon Parks used his camera as a weapon against racism and poverty, Frazier came to the realization during her undergraduate years at Edinboro University that she would also make photographs that spoke to both the general public and the art world about the state of the country.

While Frazier is comfortable calling her work social commentary, it is never didactic, aesthetically lazy or an appendage of a political agenda. It is always soulful, meticulously composed, achingly alive and suffused with abundant levels of her own empathetic and compassionate gaze.

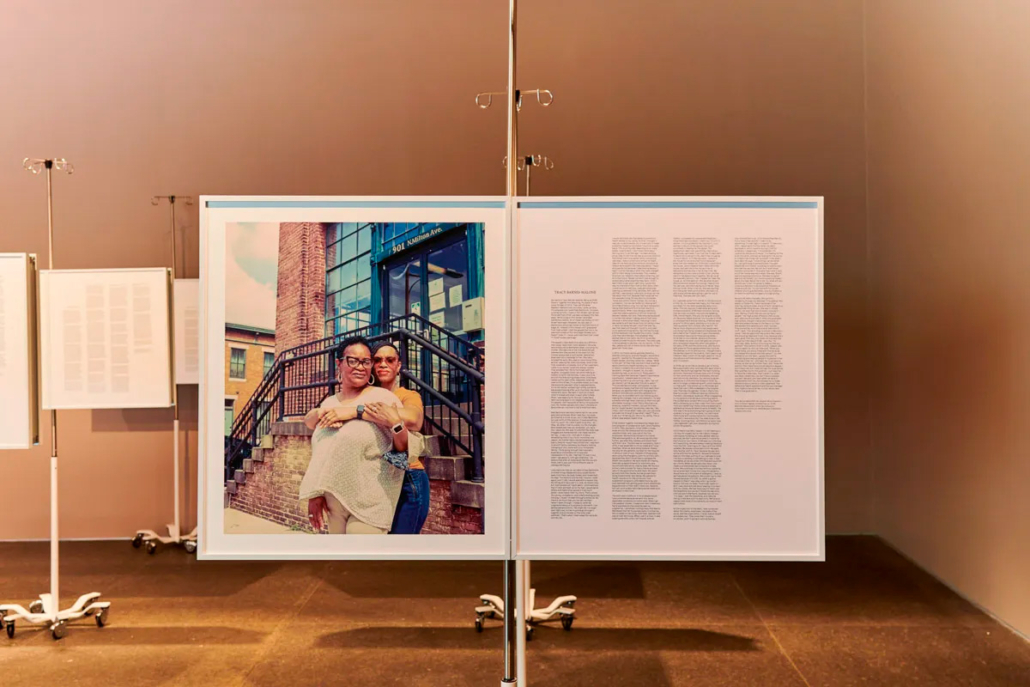

More Than Conquerors: A Monument for Community Health Workers of Baltimore, Maryland 2021-2022. © LaToya Ruby Frazier, courtesy of the artist and Carnegie Museum of Art. Photograph by Sean Eaton.

Frazier has always been inspired by art that she says addresses “the current, urgent political and economic shifts and trends in the nation that impact working class families and communities.”

“Being born and raised in Braddock, Pa., I understand that [challenge] deeply on a personal level as well as a political level,” Frazier says. “Because I grew up in the ’80s, that was me being a little girl looking at the impact of the Reagan administration’s policies on communities like Braddock.

“But then, being a young Black woman at the nexus of all of this social justice and cultural change is something that we hadn’t seen in the 21st century,” she says. “So I’ve really embraced how I’ve been born and raised. That all informs and impacts the depths with which my work takes different approaches and modes whether through photographs, writing, interviews, performance, immersive photographic installations or [workers] monuments.”

Frazier believes viewers can sense “the whole breadth of the 20 years of practice” that went into each piece.

While exceptionally well-composed and beautiful, they are not intended to make viewers feel good. They are not intended to hang over couches or reinforce the smugness of the ruling classes. The work is a tangible witness to the systemic deindustrialization that has hollowed out the American dream.

“These are [about] steel mill towns, coal mining regions, automotive industries,” she says. “What you actually see me doing is taking these micro-level experiences and scaling them up into macro-level conversations about the stories we tell around America’s great industrial past — its technical evolution.”

She also notes that her work, especially the monuments “create a safe space and opportunity for working Americans to talk about their lives and their labor and why they care about the work they do without being threatened by their employer.”

Courtesy of: NEXT Pittsburgh