In Photos of Flint and of Health Care Workers, LaToya Ruby Frazier Updates American Iconography

Art In America

by Shameekia Shantel Johnson

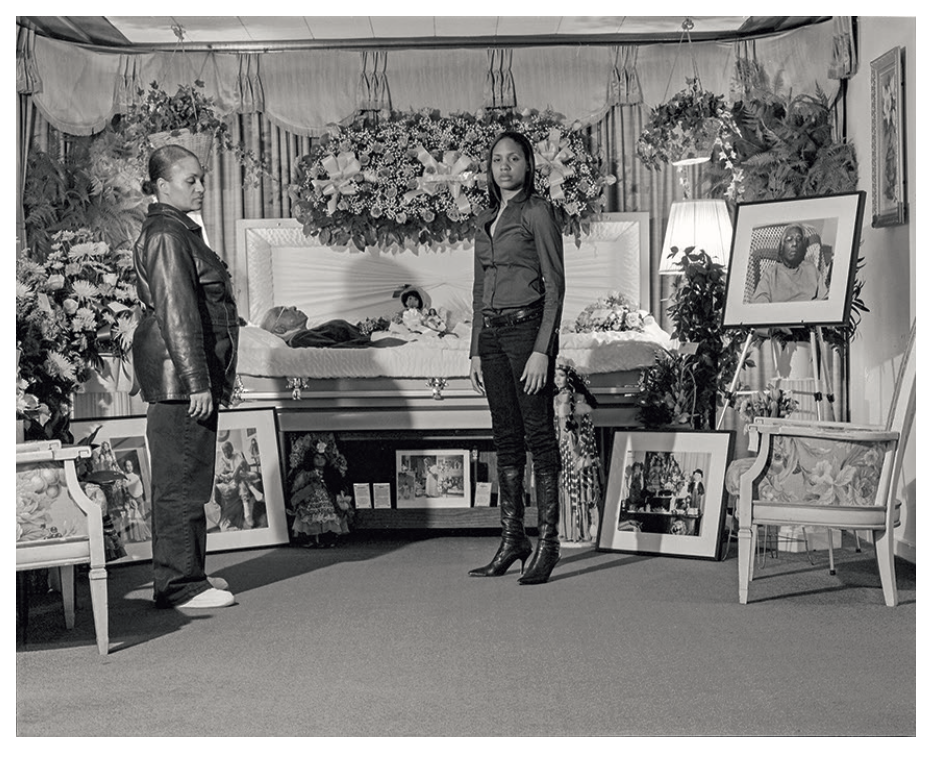

Since the early 2000s, Frazier has enlisted photography to transform everyday people and community organizers into statuesque figures.

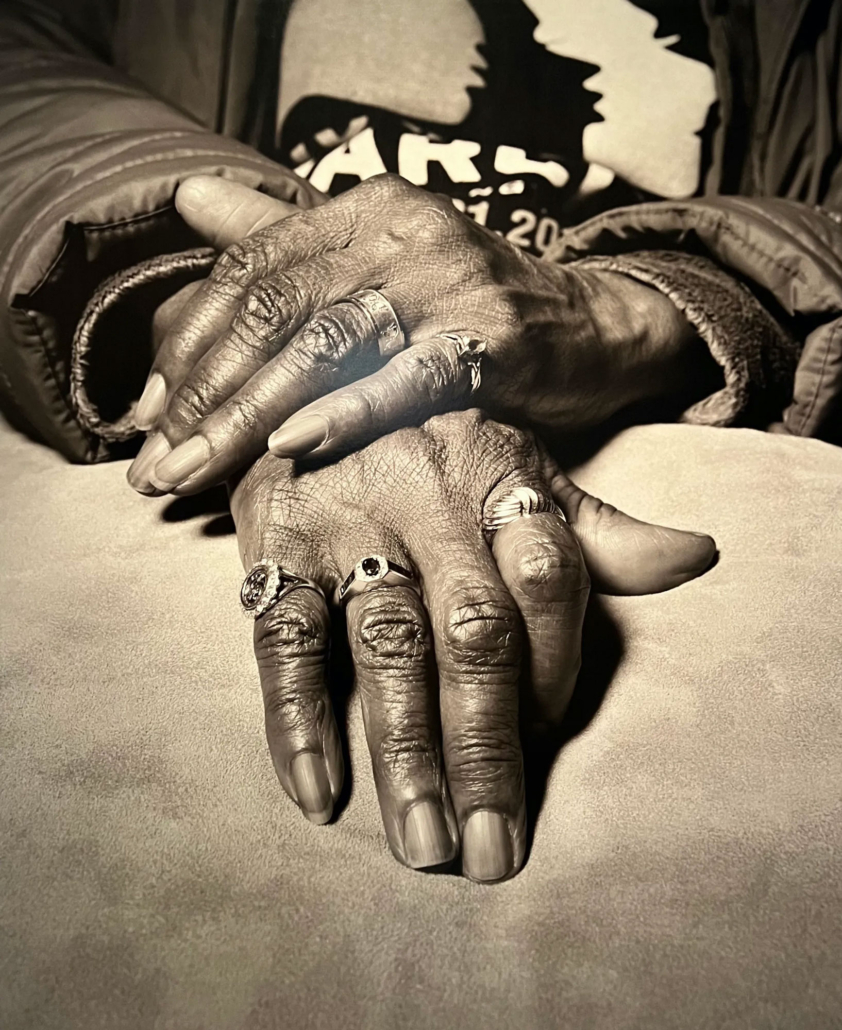

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Momme, 2008

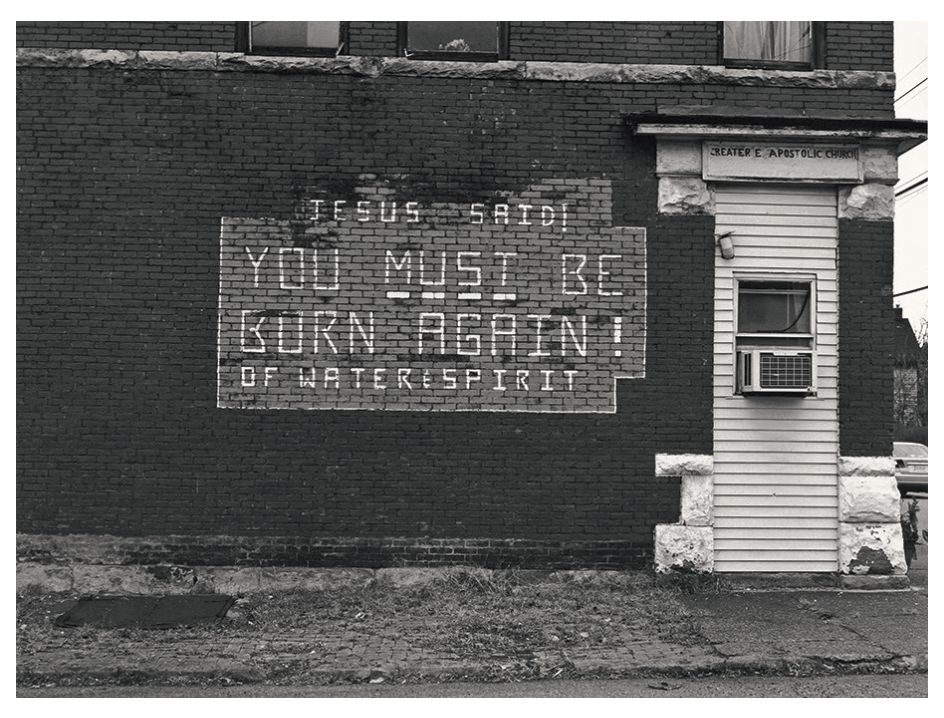

There’s nothing more American than the idioms capturing the pride of hard work and individuality, the “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” and “burning the midnight oil” slogans that drape us in the archetype of the solo pioneer. Our country’s ethos often feels like a byproduct of the ad-man age, teeming with nostalgia for a time when everything was American-made, when labor was synonymous with working-class pride rather than exploitation. In “Monuments of Solidarity,” LaToya Ruby Frazier’s first museum survey, on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York through September 7, we see the artist fashion new grammars of American identity, ones that are being formulated now, in the postindustrial boom.

Since the early 2000s, Frazier has enlisted photography to transform everyday people and community organizers into statuesque figures. Her tender portraits evoke a dedication to world-building that centers around a love ethic. Most importantly, seeing Frazier’s expansive artworks in the near collapse of an empire calls attention to the fallacies of American hubris: that our country may never tremble, or more arrogantly put, that a single leader might keep us afloat.

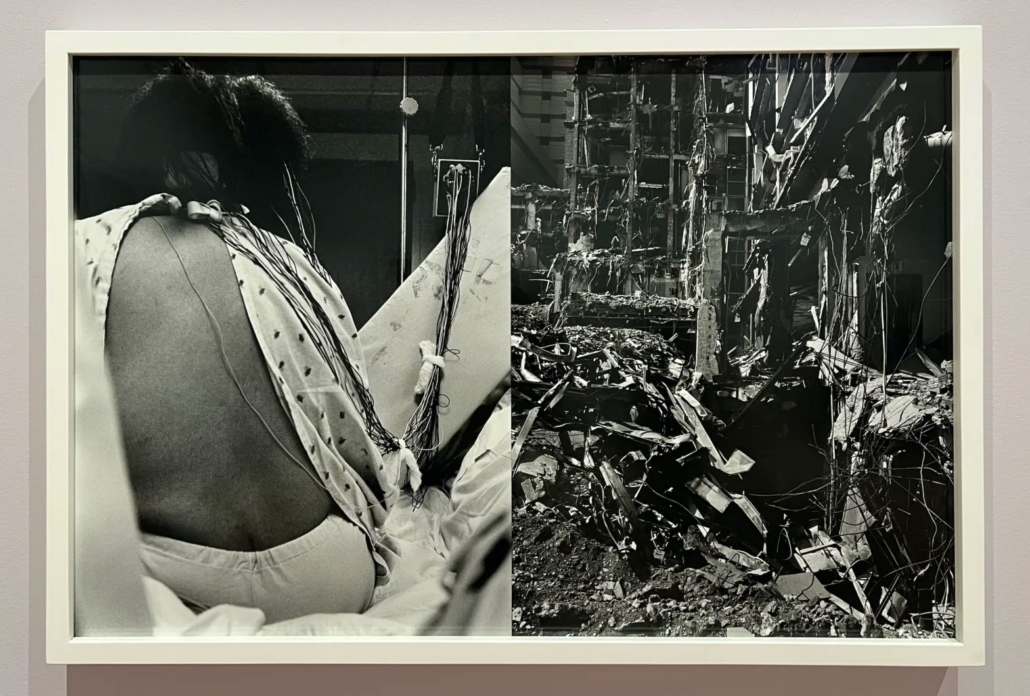

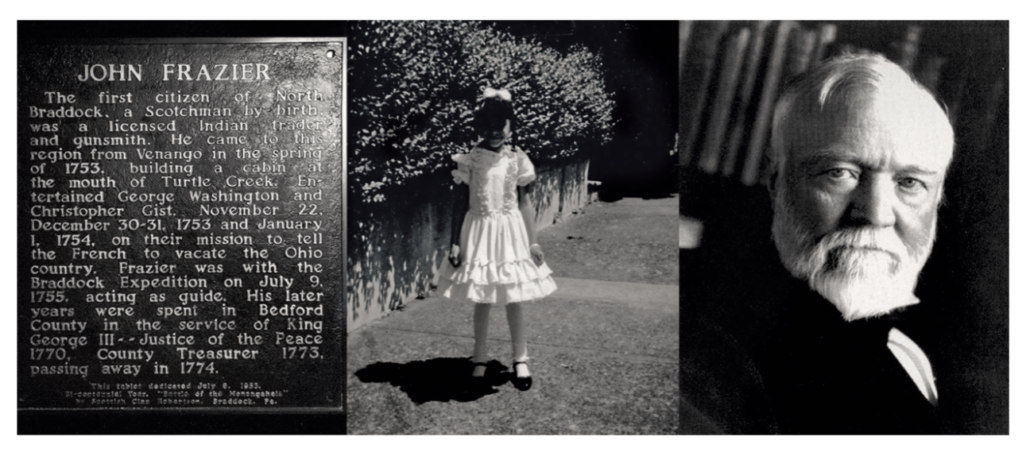

It’s bittersweet to acknowledge that the best art comes from moments of indelible pain. That is how we are introduced to Frazier’s work: at the start of the exhibition, we meet a teenage Frazier who trains the camera on herself, and on the matriarchs in her family. She orients our gaze towards three generations of women all experiencing the repercussions of poverty and ecological contamination in the industrial town of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Images and videos from her illustrious series, “The Notion of Family”—which she worked on for more than a decade between 2001 and 2014—are suspended in the air or glittered along the lavender walls that frame the predictable gentleness of feminine youth against the harsh realities of social, economic, and environmental dispositions. The black-and-white gelatin silver prints are presented on a modest scale that strikes the perfect balance between intimacy and immediacy. In Momme (2008), a petite double portrait of Frazier and her mother, Cynthia, their faces eclipse one another, aligning in such a way that they appear as one person. Self Portrait (United States Steel), 2010, pairs a color video diptych of Frazier nude from the waist up with reels of smoke from a Braddock factory looming in the air. Here, we witness the symbiotic relationship between her vulnerable body and our sickly landscape, both suffering from the chemical ills of capitalism. “The Notion of Family” is grounded in metaphors of decay, mirrors, and lineage, weaving autobiography with public investigation, a combination that remains consistent throughout her practice.

View of LaToya Ruby Frazier’s installation The Last Cruze, 2019, at The Museum of Modern Art.

Photo Jonathan Dorado/Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York

Seeing Frazier’s magnum opus of a series unfold throughout these first galleries helps solidify the importance of her legacy right away. It’s always a pleasure revisiting the catalyst that bore the beloved artist-activist, as it is an honor to glide throughout the exhibition and see how her work grew more refined in the series that follow.

[…]

Courtesy of: Art in America